Picture: Book cover of Trans Historical: Gender Plurality before the Modern.

Trans Historical is a fascinating exploration of gender-nonconforming lives lived before Enlightenment gender binaries. The contributions range from Byzantium to New England, but the book focuses on continental Europe. The perspective is mainly North American. The editors do acknowledge the limits of this perspective. Yet, the methods and approaches are useful for readers and scholars based elsewhere.

In their introduction, the editors say they ”want a proliferation of trans futures.” There is much that queer critique ”could not ’see’ about gender nonconformity, or what Carolyn Dinshaw calls a ”reading problem.” In the book, they encourage historians of gender plurality to move from focusing on individual lives to religious, legal, medical and social ”structures of power.” Religion is a key intersection – nonconformists of all kinds come up in this sphere, too. Any study of premodern lives needs to engage with theology, and the authors engage with Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and other religious traditions. Premodern Christian writing went far beyond “traditional” views of male and female roles and paths to holiness: hagiographies (lives of saints) or meditations on the trinity (one God in three persons) show multifarious understandings of gender (Coakley 2002). Law and medicine are two more key spheres that govern premodern gendered lives (Toepfer 2025). In medicine, this volume sides with Galen not Aristotle, and with practitioners, not professors. Court cases of people whose gender gets them in trouble with the law, like Elena/Eleno/Elenx de Céspedes, are some rare vernacular sources on premodern gender plurality.

The editors acknowledge how concepts of gender are shaped by language. Language includes grammatical gender and gendered pronouns (which Finnish luckily does not have). Concepts of gender are also shaped by racial and ethnic differences (which Finns have addressed less than others). As the editors say in their introduction, changing terminologies shape gender too, as do the ”putative ’newness’ of trans lives and identities.”

One joy of this book is that it explores plural gender before the Enlightenment: that is, before the scientific and statistical normal and normativity in the modern sense, and well before nineteenth century sexology or a fixed understanding of binary gender. Medieval bestiaries (illustrated books describing animals) and hagiographies, romances and travel narratives, are important sources for plural understandings of gender, such as Emma Campbell’s study of the hyena and “visualizing the trans-animal body.” These tell us as much about the culture and society through fiction and legend as the legal and medical cases do when trying to nail down facts.

The contributors aim to develop more rigorous methodologies to examine past gendered and sexual experiences. As one of the editors, Greta LaFleur says in the epilogue, looking at history from a trans perspective, we can learn from “all sorts of figures, moments, and people” about ways of understanding gender as more than a binary. In close readings of gender in their sources’ time and place, the authors give the subjects the freedom not to be trans. They call on us to attend to ”the cissexist heteropatriarchies that usually inform” historical methods in the hope that when these norms break down and decay, the ground will be fertilised for new and more fruitful ways of understanding gender to grow.

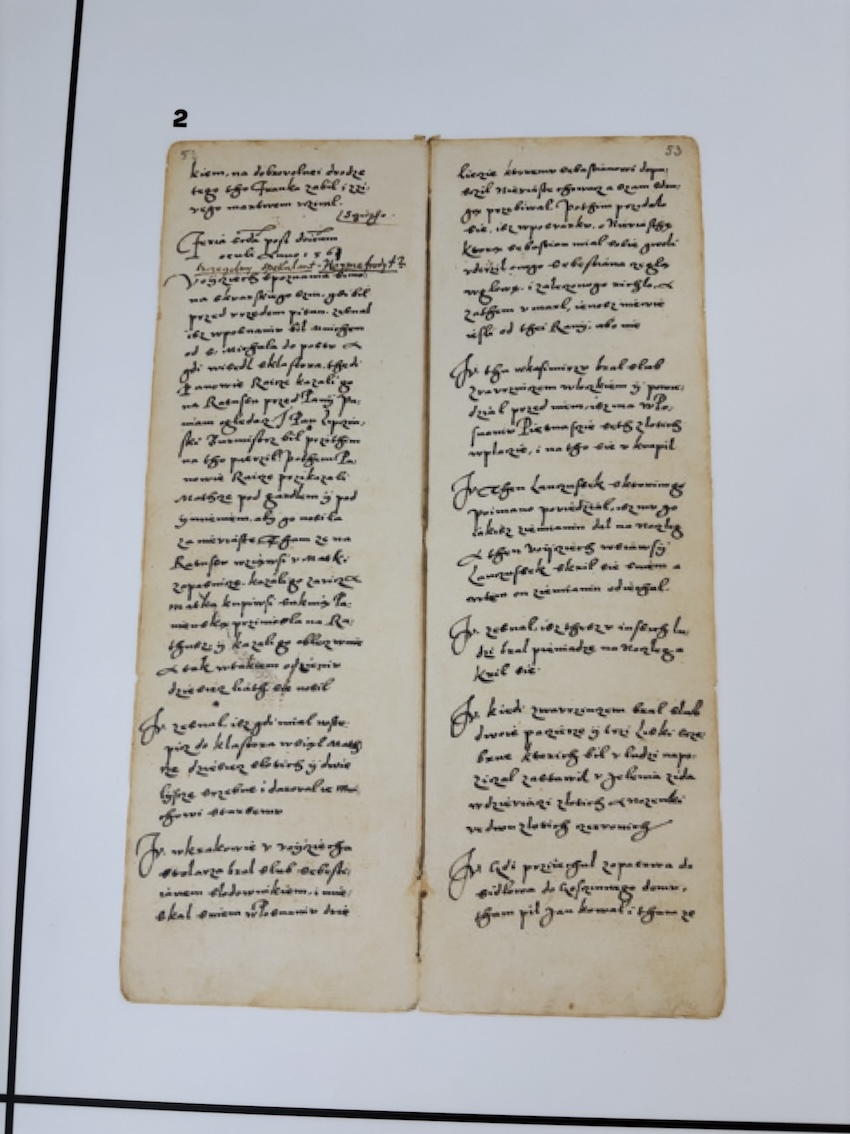

Language is of course a core theme in the book. The authors use the pronouns and attributes that the sources use to describe the protagonists. This includes words that could resonate uncomfortably to readers today, such as “hermaphrodite.” Besides pronouns and attributes, a third aspect of language is translation. Making texts out of other languages available in English decentres an Anglophone view of gender and sexuality (Baer 2020). Anna Kłosowska focuses on sources that have not been available to readers in English in her chapter on Wojciech of Poznań, presenting a fascinating early modern Polish case. Zrinka Stahuljak shows how humanism changed translation, too, reducing premodern plurality and possibility.

One strength of the book is the thick description to overcome epistemic blindness (Campbell’s chapter). The authors describe the social construction of gender roles in relations, before the modern view of the individual. Raskolnikov’s chapter on romance shows that male and female are “things that have to be learned.” Gender is constructed along intersections such as race and empire: from Sojourner Truth (Greta LaFleur’s epilogue) back to Byzantium (Roland Betancourt’s chapter). And physical ability, in Micah James Goodrich’s marvellous exploration of mayhem and mishap. But what about age? What about the (his)stories of people who aren’t young and beautiful, but still trans?

Representation is another core theme of the work. Representation includes issues of faithfulness and deception. Is the representation true or false? This relates to questions of faith, justice and health in religion, law and medicine. The authors look for cases where their sources capture transition, reveal or gloss, and conceal. Images are important here, and how they relate to paratexts, and the artists who make them. Naturalness and aberration come up here. The monstrous is something demonstrated – both words come from the Latin verb monstrare, to show. And a monster is strange, but also marvellous (see Videen 2023).

Trans and queer folks look to the past for strategies in the present, as the image of Harvey Milk, Marsha P. Johnson and Audre Lorde shows (see Wareham 2024). This book shows that it is possible to look much further back. We need transcestors, as Abdulhamit Arvas notes in the chapter on Ottoman gender variance. But scavenging, looking for glimmers and gaps (Halberstam 2018) does not always reveal what one might hope. There is invective ideology too. Trans people had to face this process of revelation and examination before the modern, too. Then as now, they refuse to conform to classifications. As Robert Mills says in the chapter on Wilgefortis, we need to accept the “enduring provisionality…and limits of our taxonomic impulses”.

The collection aims to offer correctives to earlier readings. It addresses feminist and Foucauldian misreadings and misclaimings. The authors call for “critical trans-attendance” to articulations of power (Scott Larson’s chapter). They encourage us to rethink periodization in relation to plural gender. In contexts like Finland, in contrast to many of those described in this volume, fewer early written sources survive. In these cases when few texts are available, historians might need other methodologies, like those used in memory studies (Savolainen and Taavetti 2022), to piece together a story from unofficial or partial evidence, including vernacular, material and visual sources such as oral traditions, buildings and photographs or paintings. Combining these different sources, we can read how gender plurality intersects with other premodern social relations.

In the Lutheran-dominated Nordic countries, religious conformity still impacts the body politic. Finland and our Nordic neighbours do not find it easy to acknowledge our own colonial pasts. This has consequences for our historical reading through the intersections of gender plurality. And it raises a lot of questions for historians of plural gender:

Where can we be decolonial and open to different faith traditions in our readings of gendered histories about places closer to home? How can we reread and read between gendered histories, ensure we do not repair stories and allow for stories and people to change? What premodern gender-plural sources can we translate from Latin, Swedish, Sámi languages, and Finnish? Instead of deadnaming, can we start livenaming our sources? I mean choosing not to use the past names that people rejected, but to use the names they chose and wanted to live by. Is livenaming even a word? It could be.

Picture: Wojciech of Poznań’s court case in the Polish National Archives. Kate Sotejeff-Wilson took this photo of the 1561 court documents for Wojciech Skwarski of Poznań in the Queer Museum in Warsaw in July 2025. The original manuscript is in the Polish National Archives in Kraków (Archiwum Miasta Kazimierza).

Kate Sotejeff-Wilson

The writer (PhD early modern history, UCL 2005) midwifes texts for academics and the arts. She translates into and edits in English (KSW Translations) and is interested in queer and trans history.

References

Baer, Brian James (2020) Queer Theory and Translation Studies: Language, Politics, Desire. New Perspectives in Translation and Interpreting Studies. London; New York: Routledge.

Coakley, Sarah (2002) Powers and Submissions: Spirituality, Philosophy and Gender. 1st ed. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470693407.

Halberstam, Jack (2018) Trans*: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability. Oakland, California: University of California Press.

Savolainen, Ulla, and Riikka Taavetti, eds. (2022) Muistitietotutkimuksen Paikka. Teoriat, Käytännöt Ja Muutos. SKS Finnish Literature Society. https://doi.org/10.21435/skst.1478.

Toepfer, Regina (2025) Negotiating Childlessness in the Middle Ages: Stories of Desired, Refused, and Regretted Parenthood. Translated by Kate Sotejeff-Wilson. Arc Humanities Press. https://doi.org/10.1353/book.131009.

Videen, Hana (2023) The Deorhord: An Old English Bestiary. London: Profile Books.

Wareham, Jamie (2024) ‘The Media Failed Us on Trump Last Time – as a Queer Journalist, I Refuse to Let It Happen Again’. Queer AF,. 9 November 2024. https://www.wearequeeraf.com/the-media-failed-us-on-trump-last-time-as-a-queer-journalist-i-refuse-to-let-it-happen-again/.

Sateenkaarihistorian ystävien kirjoituksia on verkkolehti, jota Sateenkaarihistorian ystävät ry julkaisee osoitteessa sateenkaarihistoria.fi/verkkolehti.

ISSN 2737-3908