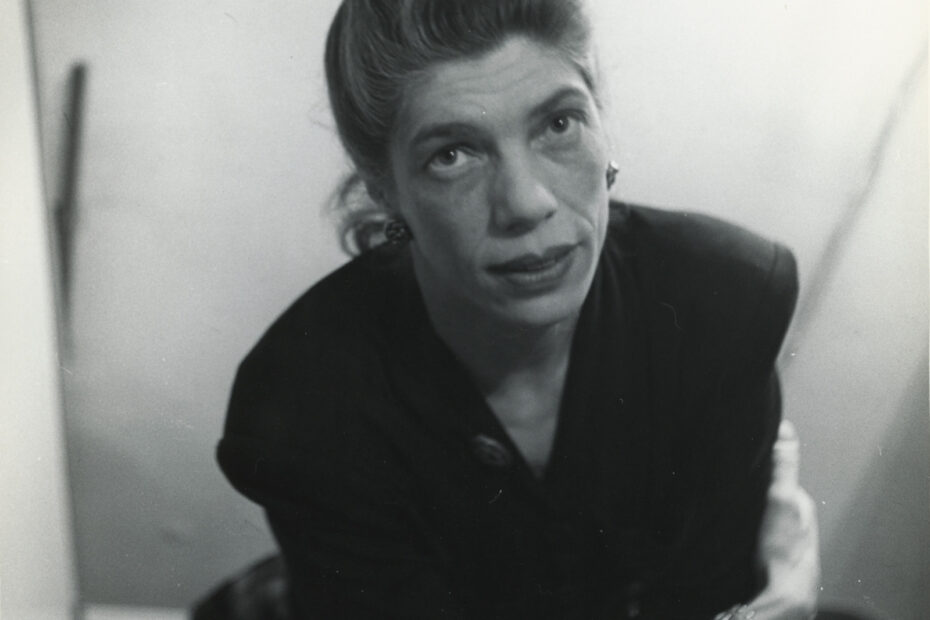

Photo of Eva Konikoff. Courtesy of Mark Saran.

Currently, there are two officially registered Jewish communities in Finland: the Jewish Communities of Helsinki, and Turku. Their membership takes up approximately 0.02 percent of the overall Finnish population –and naturally, there are a number of people outside these congregations who consider themselves to be Jewish. Rooting back to the times when Finland was part of the Russian Empire, the denominational affiliation, and the traditions of these communities are still tied to those of their ancestors: until this day, Finnish Jewish communities operate as officially Orthodox – while the practices of the membership on the individual level (that is, outside the synagogue, at home) can be significantly more diverse and flexible.

Orthodox Judaism –similarly to other Jewish denominations– is not a unified movement or branch of Judaism. It is, however, decidedly the most traditional of the denominations. As such it is known for its strict adherence to the Jewish law, which entails a traditional understanding of gender roles, and a rather rigid understanding of sexuality.

The halakhah, the Jewish law, provides a guideline on every aspect of Jewish life. It has an extensive focus on sexual practices and marriage as well. Jewish law does not disparage sex, but most Orthodox denominations that strictly follow the Jewish law only support heterosexual relations within the context of heterosexual, endogamous marriages. When it comes to questions of gender, the Jewish legal tradition identifies eight “gender designations.” Careful consideration of the legal texts may provide us with the understanding that in the Jewish thought gender is neither binary nor even a grid into which every person must be forced to fit. Rather, gender diversity may be viewed on the spectrum. Among these designations are the normative male and female gender identities also other designations, which are often referred to as “intersex” identities. Taking all this into consideration, it is rather surprising that contemporary Orthodox Jewish understandings of sexuality and gender are cis- and heteronormative –to say the least.

While in certain countries, where the size of the Jewish minority is bigger than that in Finland, questions about gender and sexuality in the Jewish context have increasingly been in the forefront of the discussions. In Finland such matters still fall somewhat onto the outside of the radar and have not yet been studied so far scientifically.

Marriage is vital in Judaism for a number of reasons. On the most fundamental level, it is often viewed as a “legal transaction,” in which the partners enter a mutually binding commitment, which is agreed upon in a marital contract, a ketubah. Of course, on other levels marriage is also a celebration of two souls being connected in companionship, with a purpose of creating a family. Marriage is, therefore, often viewed as the gateway to Jewish continuity. For most Orthodox Jewish denominations, the ideal form of marriage is heterosexual marriage between two Jewish partners, solemnized via a Jewish religious marriage ceremony.

What do we know about Finnish Jewish queer history and everyday life?

Previous studies have pointed out that while the Finnish Jewish communities have in fact operated as Orthodox over the course of their time, due to the general societal changes, and partially to the changes in the legal sense the congregational membership started to become more and more secular. This became especially prevalent in the 1950s, when one very well-documented aspect of this secularization was the growing number of intermarriages between Jews and non-Jews among the members, which caused various changes in the congregation at times. It can be assumed, that if heterosexual marriages between Jews and non-Jews resulted in heavy discussions and opposition by the congregational leadership – and in some cases the families themselves. Similarly, it can be assumed that publicly known queer relationships would have caused significantly greater problems for those engaged in them. Of course, it would be unrealistic to think that they did not exist at all. A more likely explanation is that the stigma associated with such matters has been too strong, making information publicly non-available. According to the current state of research, however, little is known or proven about such encounters, most of them stay on the level of congregational gossip and speculation.

Unfortunately, the historical aspects of queer Jewish history in Finland have not yet received much scientific attention, nor are explicit sources of these matters available in the Finnish Jewish Archives. What is known, is that of course, some aspects of queer history in Finland cross paths with local Jewish memory. These examples include for instance, the case of Mauritz (Moshe) Stiller, who is probably best known for moving to Sweden as a young adult, where he discovered Greta Garbo. His film “The Wings” (Swe. Vingarne, Fi. Siivet) is among the first long queer films in the world. The other perhaps rather famous examples are connected to Tove Jansson and her ties to local Jews: on the one hand, resulting from her heterosexual relationship with the painter Sam Vanni, and her very close friendship with Eva Konikoff have been examples of these intersecting histories. Eva Konikoff, similarly to Sam Vanni, had a great importance in Tove’s life both in terms of the expression of her artistic will and their friendship. The correspondence between the two women is well-documented, and Eva Konikoff was the recipient of a letter Tove wrote about her sexual orientation, when elaborating on her relationship with Vivica Bandler:

I don’t think I’m entirely lesbian, I have a very clear sense that it can’t be any other woman than Vi[vica Bandler], and my relationships with men are unchanged. Improved, maybe. Simpler, happier, less tense.

(Source: Moomin.com)

Vivica Bandler (née von Frenckel) Tove’s lover, a theatre director and agronomist, who got married to the Austrian Kurt Bandler in 1943. Kurt Bandler was half-Jewish, and as such had fled his homeland after the Nazi annexation and subsequently fought in the Finnish Winter War. While the relationship of Vivica and Tove had a passionate start, it did not last, and Vivica remained married to Kurt Bandler. The marriage of the Bandlers’ may very well have been a marriage of convenience for both partners: for Vivica as she got the status of a married woman, and for Kurt as he got refuge and financial support in Finland.

Contemporary challenges

Whilst due to the lack of available historical data and to the small size of the local Jewish congregations, researching queer Jewish history and present becomes particularly complicated in Finland: such research may bring up particularly sensitive matters on the congregational and on the family and individual level, which need to be carefully considered. The absence of research so far, however, does not mean that Judaism and queerness are “incompatible” with each other. Jewish identity may often falsely perceive to be solely constructed and negotiated on religious grounds, when in fact it may be affiliated to one’s perception of their own ethnic, cultural, and even political identities.

When it comes to the contemporary aspects of the intersections of queer and Jewish identities in Finland, recent scientific research has only briefly tackled some aspects of queer Jewish topics.

The most recent research pertaining Finnish Jewish everyday life – and partially focusing on e.g., family life – was the Minhag Finland project at Åbo Akademi University. The research was conducted via collecting qualitative data, namely 101 semi-structured interviews with members of the Finnish Jewish communities. While informants were not specifically asked about their gender identity or sexual orientation – as the scope of the project was not focusing on such matters – a few informants have referred to have identified themselves as sexual minorities. Additionally, a recent qualitative research project in the Manifold more project of the Finnish Institute of Health and Welfare, which focused on sexual and gender minorities among the foreign-origin populations included a number of informants who identify as Jewish and sexual and/or gender minorities. In the same project, a representative of the Jewish Community of Helsinki was interviewed in a focus-group set-up about sexual and gender minority rights in the local Jewish setting. The informants of the Manifold more project, reflected on the possibilities combining queer and Jewish identities in Finland – mentioning liturgical difficulties, such as the officiation of marriages. Both set of interviews indicate, that while there are several congregations within the Evangelical Lutheran Church that are welcoming toward sexual and gender minorities, there is an obvious lack of inclusive and egalitarian congregations in the Jewish circles. In this realm, of course, consciously disaffiliating from certain congregations – which most likely is not only a contemporary phenomenon – may be a conscious choice to avoid not only gender-segregated but often homo- and transphobic spaces.

Concerns pertaining to exclusion based on sexuality and gender are well-known problems for Jewish communities. While the laws of Finland allow for same-gender marriages to be administered, the religious leadership of the local Jewish communities does not allow such marriages to take place according to Jewish traditions. Questions around gender diversity may soon become a particularly pressing issue for the congregations as well. The liturgical life of the local congregations is governed by Orthodox traditions, the religious space in the synagogue and the prayer rooms is carefully divided along the binary, for men and women. This creates multifarious issues when it comes to everyday practices, for example when reading from the Torah for both genders, receiving a Jewish burial according to one’s perceived gender – as opposed to registered sex.

Belonging to a particular denomination or being affiliated with a certain religious tradition does not imply that the perception of religion and religious practices of individuals would always be dichotomous, and as such, it is, and it has always been possible to be meaningfully queer and Jewish as well as in Finland as anywhere else.

Mercédesz Czimbalmos

Mercédesz Czimbalmos, PhD is a senior researcher at the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL). Her main research interests include contemporary Judaism, vernacular religion, the relationship between religion and health, and gender studies. Czimbalmos defended her doctoral dissertation entitled “Intermarriage, Conversion, and Jewish Indentity in Contemporary Finland. A study of vernacular Judaism in the Finnish Jewish communities” in 2021 at Åbo Akademi University. Her most recent work (in collaboration with Shadia Rask) is the report, Sexual and Gender Minorities Among Foreign-Origin Populations in Finland. An intersectional analysis (2022) published by THL.

Sources:

Minhag Finland project. Boundaries of Jewish Identities in Contemporary Finland – “Minhag Finland”.

Moomin.com. Tove & Tooti – vuosisadan rakkaustarina – Queer-teemat Tove Janssonin elämässä ja taiteessa, Osa 3. Moomin.com.

Manifold more project. Foreign background queer individuals face struggles in the Finnish society. 2022.

Sienna, Noam: A Rainbow Thread: An Anthology of Queer Jewish Texts from the First Century to 1969. 2019.

Sisällöltään kiehtova dokumentti ruotsalaisen elokuvan yli satavuotiaasta queer-historiasta kärsii ylimalkaisuudesta, kun tv-versio on saksittu alle tuntiin. Helsingin Sanomat. 2022.

Czimbalmos, Mercédesz. Intermarriage, Conversion, and Jewish Identity in Contemporary Finland: A Study of Vernacular Religion in the Finnish Jewish Communities. Åbo, Finland: Åbo Akademi University, 2021.

Czimbalmos, Mercédesz & Shadia Rask. Sexual and Gender Minorities Among Foreign-Origin Populations in Finland. An intersectional analysis. THL Report. 2022.

Westin, Boel, ja Silvester Mazzarella. Tove Jansson: Life, Art, Words :the Authorised Biography. 2018.

Sateenkaarihistorian ystävien kirjoituksia on verkkolehti, jota Sateenkaarihistorian ystävät ry julkaisee osoitteessa sateenkaarihistoria.fi/verkkolehti.

ISSN 2737-3908